Died For My Boring Trivial Sins?

By Carl S ~

Maybe you've had my experience. I attended elementary school, and one day the teacher found a note calling him some kind of a pig. Since nobody (naturally) owned up to writing it, the class was told to stay after class, to ferret out the writer. Now, the strange thing was: I personally felt guilty for that note, even though I knew nothing about it; so guilty that, right after class, I went straight home, a mile's walk away. My mother got a phone call asking where I was. She told them I was home and asked why they called. Now, we've all heard the saying, “If you're innocent, you have nothing to be afraid of,” but I didn't believe it then and I don't believe it now. She brought out that adage. Now, most parents would send the child back to face the music. Not my mom. She asked, “Did you write it?” I told her. “No, and I'm not going back.” She believed me and backed me up. Later on, the perpetrator confessed. But 70 years later, I still wonder: why did I feel guilty for something I didn't do? And in the years since then I've wondered why innocent people walk into police stations and confess to murders they couldn't have possibly committed, since the available evidence contradicts their claims.

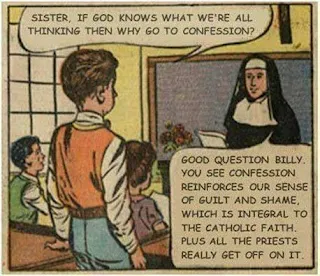

This enigma came to mind again while reading a James Agee book, “The Night Watch,” a novel about a 12 yr. old boy who, with his buddies, spends the entire Thursday night into Good Friday morning in a chapel, in a “vigil,” praying and thinking about what he has been indoctrinated to believe. Many of his “God-offending” thoughts he counters with repentant prayers; but at other times he has to admit that, in spite of what he has been told is wrong, he sees no point in feeling guilty about them. Since I spent a few intermittent years between Catholic and public schools, I'm familiar with the emphasis on guilt in parochial education. And I suspect all s.o.p. religious childhood “educating” follows the same guilt saturation to one degree or another. Not only do I see this approach as damaging (for sensitive kids), but worthless when the child starts growing up and realizes there is no god around to punish the guilty. My observations of Christian behavior lead me to conclude they don't feel guilty about many of their actions, especially cheating.

It was only after I left school when a priest told me “Jesus died for you.” I was supposed to feel grateful for this. Was I also supposed to feel guilty? Had I missed something while I was in public school instead of parochial, something about “you're personally guilty for his death because you've sinned?” (I'd even forgotten all about the thing where every human is guilty at birth!) Now, true believers may swear on a stack of bibles this is the way things are, God-wise. But, they put their emphasis on being “not perfect but forgiven,” and go on their merry way. Guilt is a serious matter to me; not easily brushed aside so blithely. I seriously try to make decisions I won't require feeling guilty about. Sure, being human means making mistakes, like wrong and stupid decisions. And it's easier to say to some disembodied fantasy-god figure or his unaffected agent, “forgive me, Lord,” rather than apologize to the person you've hurt or damaged. Those human to human guilty feelings I can accept. They’re real.

But don't attempt to tell me or try to indoctrinate my children into accepting guilt because you say a god came out of the skies to die for their “sins.” I've heard the story invented by a man who invented his own sacrificial man-god/original sin creed out of his own imagination - a man who couldn't even form a physical relationship with a woman. The “historical Jesus,“ he knew nothing of. That Jesus was executed because of his blasphemy and opposition to religious authorities, not for redemption. (He couldn't even redeem himself.) Paul's imaginary creation who died for you, for mankind, because of an imaginary sin scenario, deserves a reality-check eraser, a laser-blade burning away that carbuncle. Feel no guilt at the demise of this guilt.

Maybe you've had my experience. I attended elementary school, and one day the teacher found a note calling him some kind of a pig. Since nobody (naturally) owned up to writing it, the class was told to stay after class, to ferret out the writer. Now, the strange thing was: I personally felt guilty for that note, even though I knew nothing about it; so guilty that, right after class, I went straight home, a mile's walk away. My mother got a phone call asking where I was. She told them I was home and asked why they called. Now, we've all heard the saying, “If you're innocent, you have nothing to be afraid of,” but I didn't believe it then and I don't believe it now. She brought out that adage. Now, most parents would send the child back to face the music. Not my mom. She asked, “Did you write it?” I told her. “No, and I'm not going back.” She believed me and backed me up. Later on, the perpetrator confessed. But 70 years later, I still wonder: why did I feel guilty for something I didn't do? And in the years since then I've wondered why innocent people walk into police stations and confess to murders they couldn't have possibly committed, since the available evidence contradicts their claims.

This enigma came to mind again while reading a James Agee book, “The Night Watch,” a novel about a 12 yr. old boy who, with his buddies, spends the entire Thursday night into Good Friday morning in a chapel, in a “vigil,” praying and thinking about what he has been indoctrinated to believe. Many of his “God-offending” thoughts he counters with repentant prayers; but at other times he has to admit that, in spite of what he has been told is wrong, he sees no point in feeling guilty about them. Since I spent a few intermittent years between Catholic and public schools, I'm familiar with the emphasis on guilt in parochial education. And I suspect all s.o.p. religious childhood “educating” follows the same guilt saturation to one degree or another. Not only do I see this approach as damaging (for sensitive kids), but worthless when the child starts growing up and realizes there is no god around to punish the guilty. My observations of Christian behavior lead me to conclude they don't feel guilty about many of their actions, especially cheating.

It was only after I left school when a priest told me “Jesus died for you.” I was supposed to feel grateful for this. Was I also supposed to feel guilty? Had I missed something while I was in public school instead of parochial, something about “you're personally guilty for his death because you've sinned?” (I'd even forgotten all about the thing where every human is guilty at birth!) Now, true believers may swear on a stack of bibles this is the way things are, God-wise. But, they put their emphasis on being “not perfect but forgiven,” and go on their merry way. Guilt is a serious matter to me; not easily brushed aside so blithely. I seriously try to make decisions I won't require feeling guilty about. Sure, being human means making mistakes, like wrong and stupid decisions. And it's easier to say to some disembodied fantasy-god figure or his unaffected agent, “forgive me, Lord,” rather than apologize to the person you've hurt or damaged. Those human to human guilty feelings I can accept. They’re real.

But don't attempt to tell me or try to indoctrinate my children into accepting guilt because you say a god came out of the skies to die for their “sins.” I've heard the story invented by a man who invented his own sacrificial man-god/original sin creed out of his own imagination - a man who couldn't even form a physical relationship with a woman. The “historical Jesus,“ he knew nothing of. That Jesus was executed because of his blasphemy and opposition to religious authorities, not for redemption. (He couldn't even redeem himself.) Paul's imaginary creation who died for you, for mankind, because of an imaginary sin scenario, deserves a reality-check eraser, a laser-blade burning away that carbuncle. Feel no guilt at the demise of this guilt.